What-if’s in basic Mathematics

Who was the first person to think of eating lobster? Who invented the wheel? Some of the best ideas seem to have come after a simple What-if? moment.

Some what-if experiments are wayward, and when they work it’s just funny.

Think of Eli Cash, the not-a-genius novelist in The Royal Tenenbaums, who says about his hit novel Old Custer:

Well, everyone knows Custer died at Little Bighorn. What this book presupposes is… maybe he didn’t?

Basic math has some examples of simple what-if’s with big payoffs.

Zero and negative numbers

I imagine some figure of antiquity flashing an Owen Wilson smile and saying

Well, everyone knows you can’t subtract a number from a smaller number. What I presuppose is … maybe you can?

You can choose not to use negative numbers for day to day arithmetic tasks, but already in some simple scenarios, they’re too convenient to do without.

An example:

Corporation BigBucks would like to find out their net balance over 2020. They have offices in 30 countries, with at least 100 offices in each country.

Imagine negative numbers haven’t been invented. We can’t subtract a number from a smaller number.

Each office gets the instructions:

- For each inbound flow of money, add the amount to a running sum: Profit

- For each outbound flow, add the amount to a running sum: Loss

- Once all cashflows have been accounted for:

- If Profit = Loss, say Net Neutral

- If Profit > Loss, say Net Profit = Profit - Loss

- If Profit < Loss, say Net Loss = Loss - Profit

The country managers get the instructions: For each of the offices in the country

- If Net Neutral, ignore

- If Net Profit, add amount to running sum Profit

- If Net Loss, add amount to running sum Loss

- Once all country offices have been accounted for:

just like each office did, figure which of Profit / Loss is bigger, and do the required subtraction to summarize the result.

Perhaps, there are area managers, say Americas, AsiaPac, EMEA (Europe, Middle-East, Africa). They each get similar instructions.

At some final level, the net balance is computed, but each level needs to treat Losses and Profits separately.

Imagine the same scenario, but now we have negative numbers available.

Each office gets the instructions:

- For each inbound flow of money, add it to a running Total.

- For each outbound flow, add its negative to the running Total.

- When all cashflows are accounted for, you’re done: the result is in Total.

The country managers, and each level above them, get the instruction: add the Totals, and you’re done.

The Romans didn’t have negative numbers available. In fact, the negative numbers, and zero, originated in India and China, and were brought to the West by the Arabs in the middle ages.

Coordinates and vectors

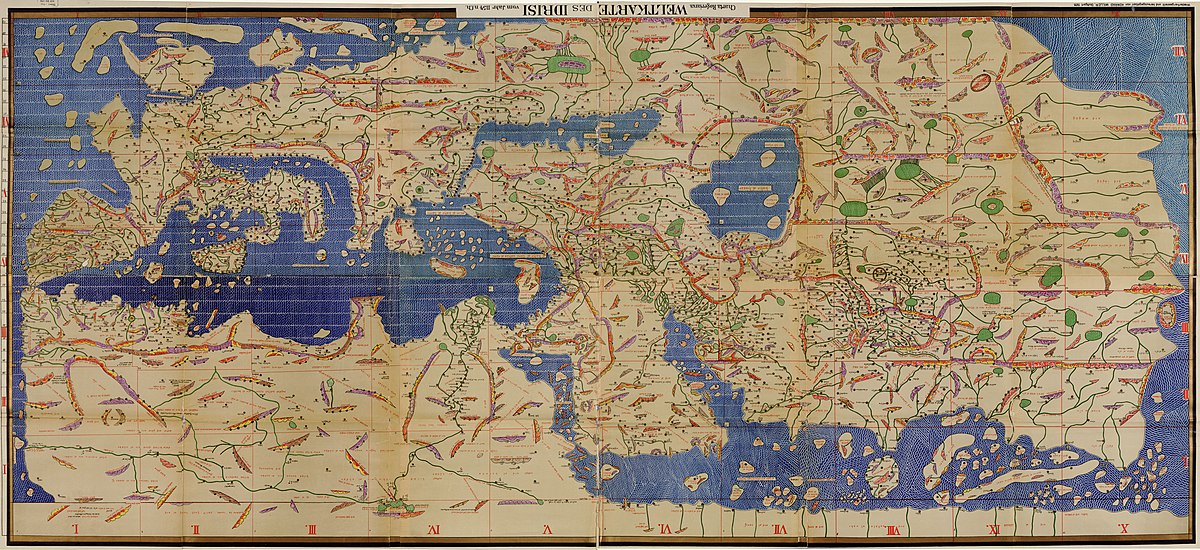

In the 17th century, two French gentlemen, Descartes and Fermat, thought of using numerical coordinates to represent points in space, and thus initiated the field of analytic geometry.

Cartographic maps existed quite a bit earlier than that, so in retrospect, it wasn’t a huge mental leap. Then again, we’re on the topic of simple ideas with a big payoff.

In pirate movies, there’s always some treasure map with obscure instructions to “go North 10 paces, then face East, jump forward with your left leg 5 times, then …”

A well known bit of basic math is that the lengths of the two smaller sides of a triangle generally don’t add up to equal the length of the big side. In the case of triangles with a right angle, the Pythagorean theorem applies, but that’s about as good as it gets.

In the above image \( d^2 = (y_2 - y_1)^2 + (x_2 - x_1)^2 \)

What if we had a “kind of number” to measure displacement in space? What if we could “add” them in a meaningful way?

We’re using coordinate pairs to represent points, but, think of representing each side of our triangle with a pair of numbers giving the side’s projections (shadows) on the coordinate axes. The horizontal side would be \( (x_2 - x_1, 0) \), the vertical side would be \( (0, y_2 - y_1)\), the hypothenuse would be \( (x_2 - x_1, y_2 - y_1) \).

What if we defined the addition of these “projection

pairs” as the sum of the components?

You can see that if we did that,

hypothenuse = horizontal side + vertical side

That’s what you call vector algebra.

The coordinates (components) of vectors can also be negative numbers. Again, you

could do without the negatives, but you’d need to handle the

four orientation combinations separately.

“(10, 45) Northeast, followed by (23, 12) Southeast, me mateys!”

Like negative numbers, vector algebra helps simplify ideas and processes. You could do without vectors, but everything would be clunkier. The benefit of good notation and good concepts is cumulative.

Now you know, when you see a pirate movie, that those instructions on the treasure map sound silly because they don’t use vectors. Not even negative numbers. That’s what happens when you don’t get a proper mathematical education.

Calculus

Calculus, that nightmare of the math-fearing. At a fundamental level, derivatives and integrals are very simple.

Say you’re taking a road trip, and your child in the back seat is jotting down the mileage markers, and the time, on a sheet of paper, or on a shiny device. The trip takes 4 hours, and by the end, you’ve traveled 200km. So, you did an average of 50km/h. Easy. But you know you paused for lunch 40 minutes, and there were road-blocks in one section of the trip, and a traffic jam in another section. So, to get a more detailed idea of your journey, the kid hands you the mileage readings and their time.

Between two consecutive readings, say reading n and reading n+1, you take the difference in mileage, and divide it by the difference in time, and that’s your average speed between those two readings.

We introduce a bit of notation:

- distance at reading n: \( d(n)\)

- time at reading n: \( t(n)\)

With this notation:

$$ \text{speed} = \frac{d(n+1) - d(n)}{t(n+1) - t(n)}$$Calculus asks, What if you had readings that were arbitrarily close? There are technicalities involved that fill up many pages, if you want to be rigorous. But they are not necessary if you just want to get the gist of things.

If we can get readings arbitrarily close, we can compute the “instantaneous speed”. Here’s how we compute the instantaneous speed at time \( t_0\):

- Get the readings at time \( t_0\) and a little, later, say time \( t_0 + h\). \( \text{speed} \approx \frac{d(t_0+h) - d(t_0)}{h}\)

- What if we make h a very small number? What if we make it 0?

First example. Imagine we had a formula giving us the distance traveled at time t. In our case: \( d(t) = 50t\).

then,

$$s(t_0) = \frac{50(t_0+h) - 50(t_0)}{h} = 50$$We already have our final answer. No need to imagine that \( h=0\).

A second example. Imagine we have a different formula for distance traveled at time t:

$$ d(t) = t^2$$Then

$$s(t_0) \approx \frac{(t_0+h)^2 - t_0^2}{h} = \frac{(t_0^2 + 2t_0 h + h^2 - t_0^2)}{h} = 2t_0 + h$$Now imagine \( h = 0\) 1. Then

$$s(t_0) = 2t_0$$Our speed is proportional to time. That’s uniformly accelerated motion.

The derivative is about figuring out “instantaneous speed” or “instantaneous rate of change” given some quantity. Speed is the derivative of the distance traveled.

The integral moves in the opposite direction. Imagine that on the road trip, you had a bunch of measurements of speed taken from your car’s speedometer, but there were no road mileage markers. To calculate the distance traveled, you’d multiply the speed readings by the time between readings, and you’d add all that up. In the integral, you ask, What if we had speed readings arbitrarily close?

From our second example, we know that if your speed is growing uniformly with time, the distance traveled grows like \( t^2\).

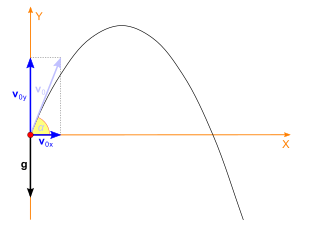

Uniformly accelerated motion happens all the time to us, due to gravity. If you fire a shell from a cannon, going back to coordinates and vectors, you can study the horizontal motion and the vertical motion of the shell independently, and then put them together.

The horizontal component of motion is easy. The horizontal speed of the shell is constant2. This was our first example. We know that the distance traveled grows proportionally to time.

The vertical component is uniformly accelerated motion, with gravity pulling the shell down to earth. We know from our second example that that motion is proportional to \( t^2\).

Putting these two motions back together, we get a parabola.

Parabolic motion

Parabolic motion

Negative numbers in calculus

In the vertical component, the shell starts going up quickly, but gravity starts decelerating it, reducing its speed. At some point, the shell stops climbing higher, and then it starts to fall. Gravity now starts accelerating it. The shell falls faster and faster towards the ground.

Complicated business, where gravity first decelerates the motion, then accelerates it.

Zero and negative numbers come to the rescue once again.

It’s probably not a surprise that the acceleration is the derivative of the speed, just as the speed is the derivative of the distance traveled.

Acceleration at \( t_0\) is approximately

$$\frac{s(t_0+h) - s(t_0)}{h}$$For our projectile, on the way up, the vertical speed is decreasing.

So, \( s(t_0+h) < s(t_0)\), so … acceleration is negative.

At some time \( t_1\), the shell stops going up, so \( s(t_1) = 0\). What happens next?

Again, acceleration is approximately

$$ \frac{s(t_1+h) - s(t_1)}{h} = \frac{s(t_1+h)}{h}$$So, \( s(t_1+h) \approx a h \) where \( a\) is acceleration.

We said acceleration was negative, and that acceleration was uniform (constant) … so this really means that the speed is negative on the way down.

Here again, the negative numbers simplify our thinking and our computations. If speed up is positive, speed down is negative. And gravity doesn’t “decelerate” upward motion but “accelerate” downward motion. Gravity always accelerates motion towards the ground. If upward distances are positive, the acceleration of gravity is negative. Let the rules of algebra handle the case analysis.

You can’t handle the truth

There’s a famous quote about mathematics that has been attributed to several famous mathematicians, among them John von Neumann.

Young man, in mathematics you don’t understand things. You just get used to them.

There’s something to it.